The musical is a magical genre, often noted for transcending reality and generating bliss and delight in contrast to mundane life (Redmond). The relationship between the musical and the individual is quite worthy of note; in the words of Leo Braudy, “The essence of the musical is the potential of the individual to free himself from inhibition at the same time he retains a sense of limit and propriety in the very form of the liberating dance” (140). Singin’ in the Rain is such a film that conveys such a feeling of liberation and freedom. Within this self-reflexive and integrated musical many elements work to gain the heightened reality that convey the sense of joy and happiness. Specifically Singin’ in the Rain, like many musicals, offers a vision of a utopian society, free from depression and misery. In Singin’ in the Rain it is the fantastical elements that generate and reinforce the utopian society that the classical Hollywood musical affirms.

The musical is a very defined genre. Rick Altman’s claim that “both intratextually and intertextually, the genre film uses the same material over and over again” (331) certainly applies to Singin’ in the Rain for more than one reason. Firstly the film was a rehash. MGM hired screenwriters Betty Comden and Adolph Green to fashion a script around a selection of songs from the Freed era of MGM musicals. Only ‘Make ‘em Laugh’ and ‘Moses Supposes’ were original songs, every other number had been seen at some point or another in the vault of previous MGM musicals (Feuer, 442). Secondly, although the film appears to be progressive in terms of its self-referential nature, it is actually only a small extension of the backstage musicals that dominated the genre in the 1930s and early 40s. Singin’ in the Rain has a specific relationship to the musical genre’s convention of utopian visions.

The musical is premised on the idea of freedom and breaking out of normal social conventions through song and dance (Chumo, 49). In operating in such a way the musical has become synonymous with the concept of utopia. The musical is distanced from various modes of realism through its nature. In the musical the sheer idea of bursting into song because of a feeling is utopian. Musical numbers have an energy that is transformative, exuberant and liberating. In this sense one can sing their way to utopia (Redmond).  The best example of this is Gene Kelly’s ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ exhibitionist number which transforms the feeling of being in love into a song and dance expression of pure happiness (Wollen, 28-29). The feeling of utopia associated with musicals often occurs at heightened moments of reality. Utopia is outside of the real; like Kelly singing in the rain, it takes elements of fantasy and transports these into expressions of utopia.

The best example of this is Gene Kelly’s ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ exhibitionist number which transforms the feeling of being in love into a song and dance expression of pure happiness (Wollen, 28-29). The feeling of utopia associated with musicals often occurs at heightened moments of reality. Utopia is outside of the real; like Kelly singing in the rain, it takes elements of fantasy and transports these into expressions of utopia.

Singin’ in the Rain lays the groundwork for producing a utopian society through its setting. As it is shown repeatedly in the DVD extras, the way the film was conceived lead to the setting of Hollywood. Hollywood as a non-representational notion is the perfect manifestation of the American Dream, a myth that is realised in the form of success and happiness. Tinseltown, in this instance, is supposed to represent more than just a myth, it is meant to represent a potential reality. This concept of Hollywood is shown in Hollywood’s frequently circulated account of success and stardom; the story of A Star is Born. Several versions of this film have been made and the regularity in which similar narratives have emerged make its mythology central to the understanding of Hollywood’s relationship to its audience (Maltby, 151). Singin’ in the Rain uses this constructed mythology as a given background to the rise of Don Lockwood and as a tool to gain the acceptance of Kathy Seldon’s rise to become a celebrated actress.

Singin’ in the Rain effectively produces two versions of Hollywood. While both exist in the fictional realm, the “Broadway Ballet” is fantastical as well as fictional. The “Broadway Ballet” contains an accelerated narrative of a talented character who arrives in a foreign town and finds himself gaining success and falling in love. Through montage we see his rise to access the American Dream and be joyful and infectious come the end of the sequence. The narrative resembles that of a star’s rise to fame in Hollywood, and therefore the Broadway setting is not unlike Hollywood in the sense that it is a place in which dreams can be realised. The Hollywood in which the film’s primary narrative takes place is typical of pro-Hollywood representations. Villains are identified and discarded, and talent is identified and established. In fact the two Hollywood’s are not dissimilar. Both present a lively, diverse world full of colour, texture, light and movement; a utopian location where the American Dream can be realised.

Within this fantastical setting the fantastical elements work to reinforce the utopian backdrop that is Hollywood. The most striking of these elements is the “Broadway Ballet”, which makes no attempt to claim any hold on reality. Its playful use of colour, abstract settings, montage, costume and dream sequences all support its context as being of the imagination. The “Broadway Ballet” is the absolute expression of utopia for this reason. It affirms a feeling of happiness, which culminates with Gene Kelly’s final declaration as he soars high in the air with a radiant smile, or as Roger Ebert says, “[it] pulses with life” (422). More specifically, the idea of utopia is inherent in this sequence because of the narrative. The protagonist of the sequence is faced with difficult odds but transcends them by living out the American Dream, finding success. The only thing that is missing is love, but this is resolved by the final dance that replaces the love of a female companion with the love of life, in particular love of art: “gotta dance!”

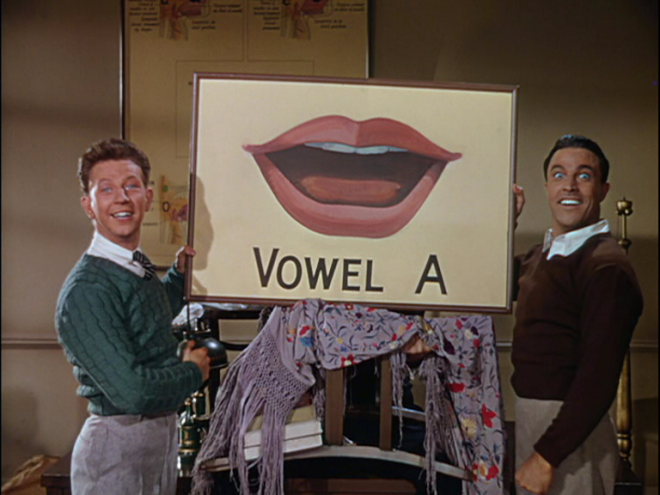

Other fantastical elements are less apparent. They operate in alternative ways, affirming Baz Luhrmann’s claim, in his audio commentary, that Singin’ in the Rain is winking at its audience. The first of these elements is right at the beginning of the film setting the tone of the film to come and simultaneously establishing character. It is the opening sequence in which Don Lockwood narrates flashbacks detailing his career. These flashbacks are unique as the camera operates outside of Don’s point of view and subjectively opposes the audio track with contradictory visuals. By “contrast[ing] the self-aggrandizement of the voice-over with the presumed true story shown in the visuals” (Feuer, 445) the film draws attention to its self-reflexivity and reminds the audience that they are watching a film. This structure is repeated later on when the process of producing Lena’s voice is demystified (Maltby, 68) and the audience again is made aware of being winked at.

These flashbacks, which dominate the opening exposition of the film, are fantastical in the sense that they illustrate the opposition between what is said and what is seen. But they also operate outside the temporal order of the film and furthermore challenges the way the camera typically operates. It is the only time in the film where the camera works in opposition to the characters. Throughout the film the camera is obliging. When ‘anti-film’ elements are exposed, in other words when the techniques of film are exposed, it is all in cooperation with the characters or in the best interest of the characters. In the flashbacks the camera exposes the truth in opposition to the characters. Through doing so the combination of the audio and visual elements builds the idea of winking at the audience and therefore the notion of utopia. The world the flashbacks build is a world that aware of what it is doing because we already know the final destination of Hollywood stardom. In this sense it is utopian, it is an accessible world where the American Dream can be lived.

Thomas Schatz identifies a tension in the musical, between “object and illusion, social reality and utopia” (188). This concept he says is worked out on two levels, the first being the “overall plot structure” resolved in the denouement. The second is “at numerous points in the narrative itself when the characters transcend their interpersonal conflicts and express themselves in music and movement” (188). The idea of characters breaking into song and performing, spontaneously, in perfect unison is a utopian ideal. Reality is transcended every time characters launch into musical numbers; where is the music coming from? How do they know the words? How do they all know the steps? These questions are not relevant because the musical uses the utopian realm where everything is ‘right’.

The musical numbers are fantastical and produce utopian ideas through their manner. When Don sings “You Were Meant For Me” on the empty soundstage to Kathy, it is an example of how the utopian ideals emerge from breaking into song. Firstly it is important to note that Don struggles with articulating his feelings, he cannot tell Kathy that she was meant for him in the ‘real’ world. Instead he needs the artificiality of a studio as a setting to sing and dance and express his true feelings. In other words he needs a setting in which utopian ideals are accepted, where he is capable of expressing his love. Kelly builds the idea of a imaginary world by “employing every cinematic trick to add to the illusion of romance that he wants to convey” (Feuer, 448). Only once the world of the imagination has been constructed can Don sing “You Were Meant For Me”; even though he draws attention to the artificiality of the situation, we cannot doubt his sincerity because he is presenting a representation of utopia.

According to Thomas Schatz, the musical’s “gradual narrative progression toward… the principle performer’s embrace project a utopian resolution” of the conflict between “object and illusion, between social reality and utopia” (188). More specifically and more pertinent to Singin’ in the Rain is his proposal that these films offer audiences “utopian visions of a potentially well-ordered community.” The community represented in Singin’ in the Rain is certainly one that holds great order; it expels Lina when her lack of talent is coupled with her scheming to bring down our heroes, and embraces Kathy for her good spirit and wholesome heart. Don and Cosmo are established as good people from their first appearance. Their friendship, from their togetherness at the premiere and in the flashbacks, is primarily what draws the audience to them as well as being in opposition to Lina.

The community that Singin’ in the Rain creates is in fact an “imagined community”. Benedict Anderson writes on this idea is regards to nationalism, but his ideas are relevant to Singin’ in the Rain. He says, “Communities are distinguished, not by their falsity/genuineness, but by the style in which they are imagined” (6). This community that dominates the narrative of Singin’ in the Rain is constantly seen in the fantasy realm, and simultaneously through this style, generates a community that adheres to these “utopian visions”. Lina never appears in any of the fantasy elements already identified; she is not part of this community of Don, Kathy and Cosmo. The plot structure is simply a backdrop for the playful fantastical showcase, and within this framework a utopian community is created, an “imagined community” that succeeds in affirming the American Dream.

Singin’ in the Rain is certainly typical of Hollywood musicals in the sense that it produces a utopian version of American society. It primarily succeeds in this regard through its use of fantasy, dream sequences, flashbacks and its song and dance numbers. In doing so a community is created, an “imagined community” which is selfish in its concerns and callous in its criteria. But to the Hollywood musical the main concern is enjoyment and fun. Singin’ in the Rain is sometimes accused of being thematically banal (Maltby, 66), but the utopian reality is Singin’ in the Rain is only aiming to be entertainment for entertainment’s sake.

Bibliography

Altman, Rick. The American Film Musical. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1987.

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities. London, New York: Verso, 1991.

Braudy, Leo. The World in a Frame: What We See in Films. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

Chumo, Peter N. “Dance, Flexibilty, and the Renewal of Genre in Singin’ in the Rain”. Cinema Journal, Vol. 36, No. 1 (Autumn, 1996), pp. 39-54.

Ebert, Roger. The Great Movies. New York: Broadway Books, 2002.

Feuer, Jane. “Singin’ in the Rain” in Geiger, Jeffrey and R. L. Rutsky (eds.) Film Analysis: A Norton Reader. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2005.

Herschfield, Joanna. “Dolores del Rio, Uncomforatbly Real: The Economics of Race in Hollywood’s Latin American Musicals” in Daniel Bernardi (ed.) Classic Hollywood, Classic Whiteness. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001. pp. 139-156.

Maltby, Richard. Hollywood Cinema. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003.

Redmond, Sean. “Musical Utopia: Hollywood Escapism”. Lecture presented at Victoria University of Wellington. 19 March 2007.

Schatz, Thomas. Hollywood Genres: Formulas, Filmmaking and the Studio System. New York: Random House, 1981.

Wollen, Peter. “Singin’ in the Rain.” London: BFI, 1992.

Filmography

Singin’ in the Rain (Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly, USA, 1952)

A Star Is Born (William A. Wellman, USA, 1937)

A Star Is Born (George Cukor, USA, 1954)

A Star Is Born (Frank Pierson, USA, 1976)